Galois Connections and Nullstellensatzen

(The idea for this post is due to this tweet by @sarah_zrf)

Hilbert’s Nullstellensatz

Consider the ring of complex polynomials in \(n\) variables, \(\mathbb{C}[x_1,x_2,\dots x_n]\). The elements of thing ring can be viewed as functions \(\mathbb{C}^n \to \mathbb{C}\). Given a polynomial \(f\), we can think of it as an equation in \(n\) variables - a solution to the equation is a tuple \((a_1, \dots a_n) \in \mathbb{C}^n\) so that \(f(a_1,\dots ,a_n) = 0\). Let \(V(f) \subseteq \mathbb{C}^n\) be the set of solutions.

Given a set of polynomials \(S \subset \mathbb{C}[x_1,\dots x_n]\), let \[V(S) = \{(a_1, \dots a_n) \in \mathbb{C}^n \mid f(a_1,\dots a_n) = 0,\ \forall f \in S\}\] be the set of solutions to the system of equations given by \(S\).

This gives a mapping from subsets \(S \subset \mathbb{C}[x_1, \dots x_n]\) to subsets \(U \subset \mathbb{C}^n\). We can also go the other way - given such an \(U\), let \(I(U)\) be the set of \(f\) such that \(f(a) = 0\) for all \(a \in U\). (We are now writing \(a := (a_1,\dots a_n)\) for brevity).

Now \(V\) and \(I\) enjoy the following very special properties:

- They are both order-reversing - if \(U \subseteq U'\) then \(I(U') \subseteq I(U)\), and the same for \(V\).

- \(S \subseteq I(V(S))\) and \(U \subseteq V(I(U))\).

This means that \(I\) and \(V\) forms a Galois connection (nlab) - a dual adjunction between two posets. This implies a bunch of interesting things. One of the most important is that the mapping \(S \mapsto I(V(S))\) is a closure operator, meaning that in addition to the above inequality, \(I(V(I(V(S)))) = I(V(S))\). In fact for anything of the form \(I(U)\), we have \(I(V(I(U))) = I(U)\).

This Galois connection is the key to algebraic geometry. It allows us to analyse algebraic things (subsets of a ring) in geometric terms (subsets of a space). So it would be really good if we could understand this thing. In particular, what is the closure operator \(S \mapsto I(V(S))\)?

It’s pretty clear that \(I(V(S))\) must be an ideal - if \(f(a) = 0\) for all \(a \in V(S)\), then \(f(a)g(a) = 0\) too (and if \(f(a) = g(a) = 0\), then \(f(a) + g(a) = 0\)). So an obvious guess would be that \(I(V(S)) = (S)\), the ideal generated by \(S\).

But this turns out not to be true - there’s one more thing we need to close off \(S\) under to make this work. Namely, if \((f^2)(a) = f(a)^2 = 0\), then also \(f(a) = 0\). So if \(f^2 \in I(V(S))\), then \(f \in S\) (and similarly for \(f^n\)). \(I(V(S))\) is a radical ideal - specifically, it is the radical \(\sqrt{(S)}\) of the ideal generated by \(S\). This statement is Hilbert’s Nullstellensatz (“zero locus theorem”, see wikipedia, nlab)

Gödel’s Nullstellensatz

Let \(\mathcal{L}\) be a first-order language, i.e a collection of function symbols \(f_1,f_2,\dots\), each with a specified arity, and /relation symbols \(R_1,R_2,\dots\), also each with a specified arity1.

An \(\mathcal{L}\)-structure is a set \(M\) equipped with a function \([f_i]_M : M^n \to M\) for each \(f_i\), where \(n\) is the arity of \(f_i\), and a subset \([R_i]_M \subset M^n\) for each \(R_i\), where \(n\) is again the arity.

A first-order formula in \(\mathcal{L}\) is a formula built up out of the function symbols, variables, and the connectives \(\forall, \exists, \vee, \wedge, \neg, =\). A model \(M\) satisfies the formula if the formula is true when interpreted in the usual way for the model.

A theory is a set of formulas. Given a theory \(T\), let \(Sat(T)\) be the set of models that satisfy each formula in \(T\). Given a set of models \(\mathcal{M}\), let \(Tru(\mathcal{M})\) be the set of formulas that are satisfied by each model.

Then it’s not hard to see that \(Sat\) and \(Tru\) form a Galois connection between sets of formulas (theories), and sets of models. What is the closure operator on theories induced by this Galois connection? In other words: Start with a set of formulas. These formulas pin down a set of models, namely the models that satisfy all those formulas. Now almost certainly some more formulas are going to happen to be true for all these models. For example, if \(\phi \wedge \psi\) is a formula in \(T\), then also \(\phi\) is going to be true for every model - so \(\phi \in Tru(Sat(T))\). In general, any formula which is provable using the normal rules of logic from formulas in \(T\) is going to be in \(Tru(Sat(T))\). This is because the normal rules of logic are sound - if you can prove something from true premises, it’s true. And in fact, this suffices! To be precise, \(Tru(Sat(T))\) consists exactly of those formulas that are provable using the normal deduction rules of first-order logic from \(T\). This is a celebrated theorem of Gödel (nlab, wikipedia). Since it has the same formal structure as Hilbert’s Nullstellensatz - characterizing the closure operator induced by a Galois connection - we might call it Gödel’s Nullstellensatz. (It is usually called the completeness theorem).

Quillen’s Nullstellensatz

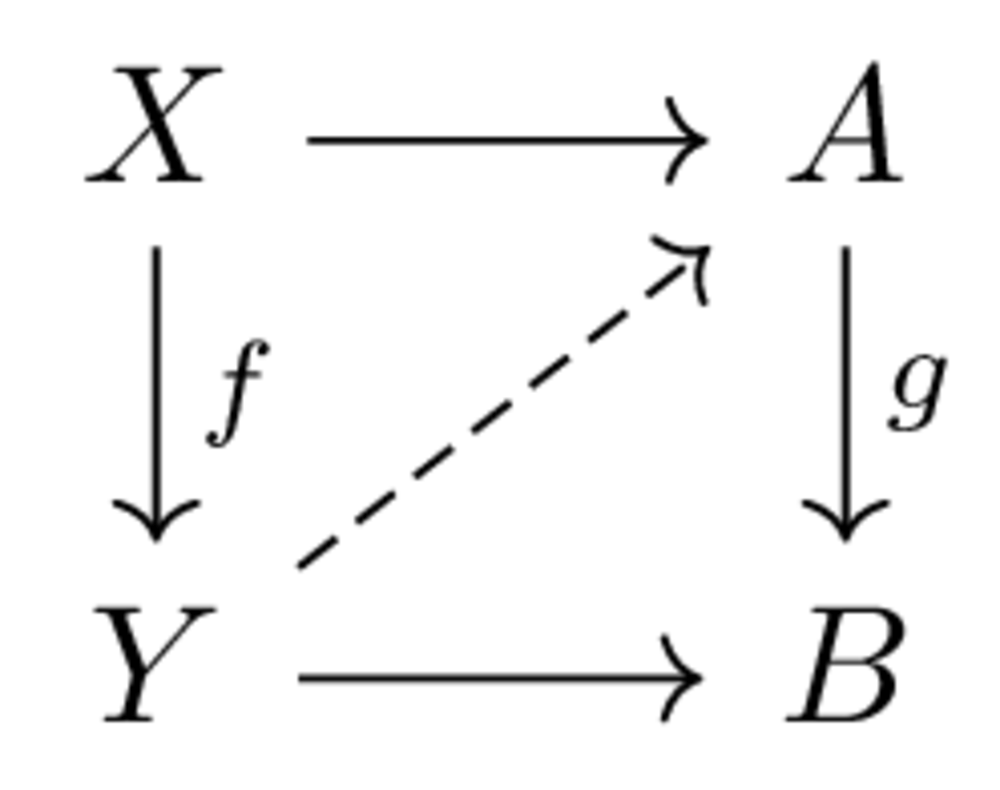

Fix a category \(\mathcal{C}\). Let \(f: X \to Y, g: A \to B\) be morphisms. We say that \(f\) has the left lifting property with respect to \(g\), and that \(g\) has the right lifting property with respect to \(f\), if, for each diagram of this form, if the outer square commutes, there exists a dashed arrow making the triangles commute as well:

Given a class \(S\) of morphisms in \(\mathcal{C}\), let \(LLP(S)\) be the class of morphism with the left lifting property with respect to all morphisms \(f \in S\), analogously \(RLP(S)\).

It is again not hard to see that \(RLP\) and \(LLP\) form a Galois connection from the collection of subclasses of morphisms in \(\mathcal{C}\) to itself. What is the closure operator \(LLP(RLP(-))\)? This is probably a bit harder to motivate than the previous examples, but understanding it is important in model category theory.

As before, we can try to find some constructions that \(LLP(RLP(-))\) is certainly closed under:

- Pushouts, in the sense that if \(f: X \to Y\) is in \(LLP(RLP(-))\), and \(g: X \to Z\) is any morphism, the induced \(Z \to X+_Y Z\) is also in there.

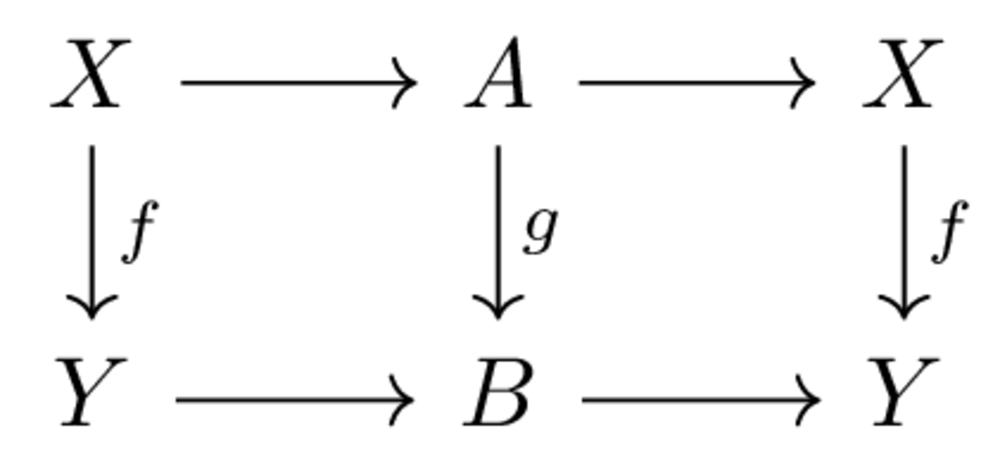

- Retracts: given a commutative diagram

where the horizontal composites are identities, if \(f\) is in the class, so is \(g\)

where the horizontal composites are identities, if \(f\) is in the class, so is \(g\)

- Transfinite composition: given a sequence \(X_0 \to X_1 \to \dots\) with each map in the class, the maps to the colimit \(\operatorname{colim}_i X_i\) are also in the class (here this diagram can be indexed by any ordinal).

Each of these proofs is essentially by a diagram chase.

A class closed under all these constructions is called saturated. Then we have Quillen’s Nullstellensatz (which is confusingly usually called the Small object argument): If \(\mathcal{C}\) is locally presentable, and \(S\) is a small set, then \(LLP(RLP(S))\) is the smallest saturated class containing \(S\).

-

I guess you can actually dispense with the function symbols if you want ↩︎